Arabic and The Story of the Qur’ān

What is the relationship between literacy, Islam and the Arabic language?

According to Islamic tradition, the Qur’ān is a book of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. It did not come to him in the form of a complete book but rather in parts over a period of several decades. The first part was revealed in 610 at Jabal an-Nur ‘The Mountain of Light’ near Mecca when the Prophet was forty years old. A few years later he began his public preaching.

Thereafter, different parts continued to be revealed to him until his death in 632. Before the time when the Qur’ān was revealed, the Egyptians had already invented a good writing material made from the papyrus plant. Whenever any part of the Qur’ān was revealed, scribes wrote it down on papyrus or qirṭas in Arabic.

During this process, people also committed the verses to memory so that they could recite them during prayer.

Note: The word qur’ān means ‘recitation’ from the Arabic root qr’ ‘to read aloud.’

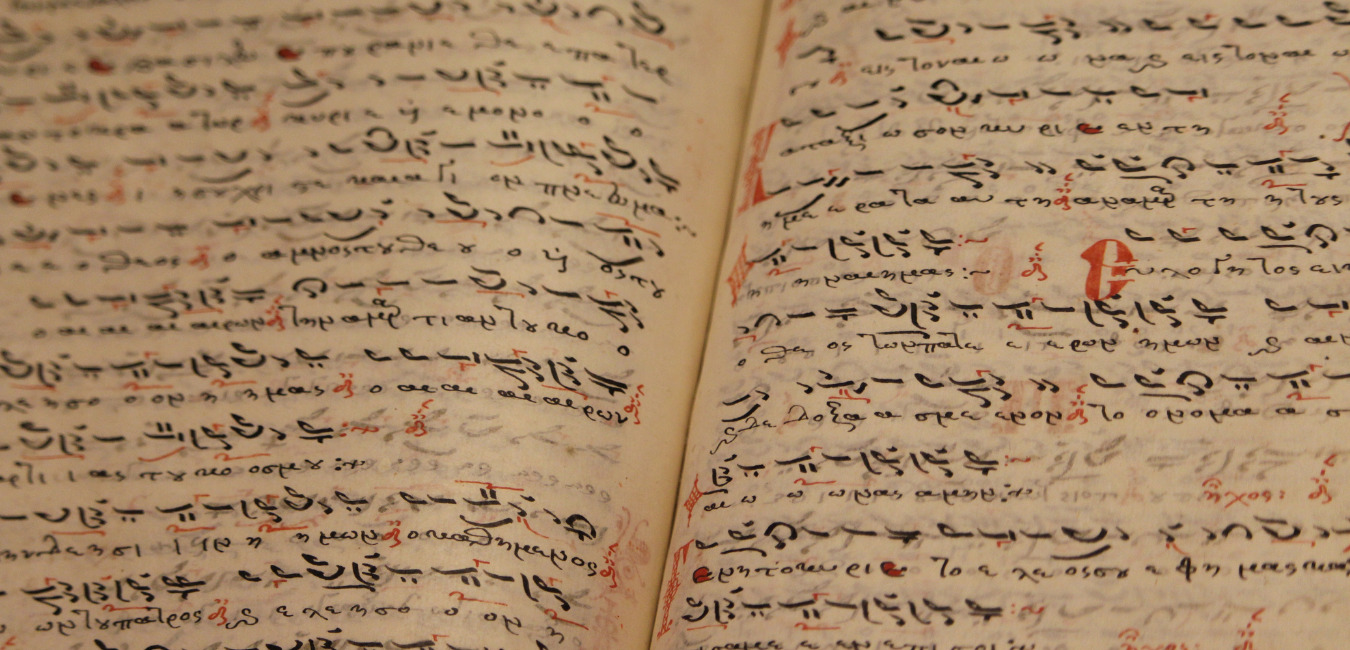

11th Century North African Qu’ran on display in the British Museum. Photo Credit: LordHarris. Authorized for distribution under Creative Commons.

Thus, the Qur’ān continued to be simultaneously memorized and written down, and this method of preservation continued throughout the lifetime of the Prophet.

The most important part of this story, from the point of view of the present chapter, is the fact that the Prophet is said to have been illiterate. The belief in Mohammad’s illiteracy secures the belief in the Qur’ān as the word of God in two ways.

First, Muhammad’s illiteracy underscores his simplicity, making him an appropriate conduit through which the word of God could be revealed.

Second, Muhammad’s illiteracy preemptively removes doubt that these words could come from a source other than God, because an illiterate man could not have created a work of such beauty and complexity as the Qur’ān.

History tells us that Muhammad was a successful merchant before his call as a messenger prophet, so he must have known how to count. During his time, letters were used to represent numbers in Arabic, as they were in all Semitic languages, including Hebrew.

Note: The use of letters for numbers in the Semitic languages is similar to the way some Roman numerals came from the Roman alphabet, for instance C from the first letter of centum ‘hundred’, a root found in the word century, and M stands for millennium ‘thousand.’

So it is possible that Muhammad knew how to write and record a transaction. Our purpose here is not to offer an opinion on the state of Muhammad’s literacy. It is rather to emphasize the fact that, despite potential evidence to the contrary, the belief in Muhammad’s illiteracy is bound to the conception of the Qur’ān as the direct word of God.

The further implication is that once the divine word has passed through the human agent, the writing down of those words can be regarded as a sacred act. It is but a small step to make the inference that writing itself is a divine creation.

The story of the Qur’ān serves three purposes for this chapter.

First, it illustrates the intertwined relationship between religion and the written word.

Second, it suggests the power of the written word, and this power, as we have just seen in the previous chapter, circulated forcefully enough throughout the eighteenth century in the form of print capitalism to reinforce a new political entity known as the nation-state. In this chapter, we will see that the power of the written word as the word of God often goes hand in hand with political power.

Third, the story of the Qur’ān brings attention to the dynamics of orality and literacy in that the development of religious tradition drives not only particular linguistic practices (prayers, chants, etc.) but also the very scripts used to represent languages.

See also: Languages in the World Blogs

From Chapter Five, The Development of Writing in the Litmus of Religion and Politics. Languages in the World. How History, Culture, and Politics Shape Language. (affiliate) Julie Tetel Andresen and Phillip Carter. November 2015. Wiley-Blackwell.

From Chapter Five, The Development of Writing in the Litmus of Religion and Politics. Languages in the World. How History, Culture, and Politics Shape Language. (affiliate) Julie Tetel Andresen and Phillip Carter. November 2015. Wiley-Blackwell.

Categorised in: Adventure, Language, Writing

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment